You are here: Home1 / Perfluorooctanoic acid PFOA-Teflon

Regardless of how it gets into our bodies, once there,

PFOA stays—quietly accumulating in our tissues – for a lifetime.

The toxic legacy that will stick around forever.

The toxic legacy that will stick around forever.

… PFOA could cause health problems such as cancer, birth defects, and liver damage …

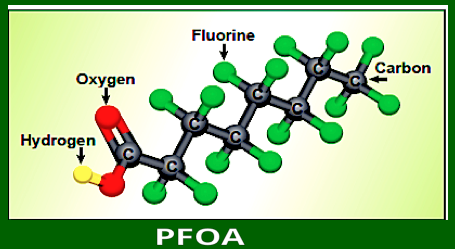

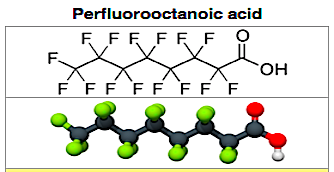

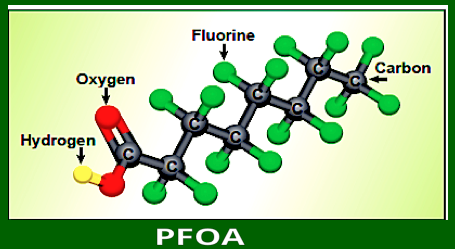

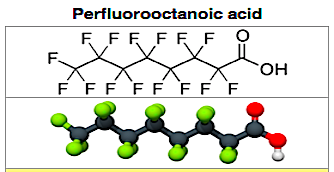

[Note: The ‘Fs’ in PFOA is code for Fluoride]

Congresswoman Pat Schroeder was scrambling eggs, one day back in 1984, when she coined one of the most durable political metaphors of our time. Her 1984 description of Ronald Reagan as “The Teflon President” became instant vernacular, attaching itself to everyone from “Teflon Tony” Blair to “Teflon Don” John Gotti.

It is all the more ironic, then, that our favorite metaphor for bad press that won’t stick comes from a product whose toxic legacy will stick around forever. Teflon, it turns out, gets its nonstick properties from a toxic, nearly indestructible chemical called PFOA, or perfluorooctanoic acid. Used in thousands of products from cookware to kids’ pajamas to takeout coffee cups,

PFOA is a likely human carcinogen, according to a science panel commissioned by the Environmental Protection Agency. It shows up in dolphins off the Florida coast and polar bears in the Arctic; it is present, according to a range of studies, in the bloodstream of almost every American—and even in newborns (where it may be associated with decreased birth weight and head circumference). The nonprofit watchdog organization Environmental Working Group (ewg) calls pfoa and its close chemical relatives “the most persistent synthetic chemicals known to man.” And although DuPont, the nation’s sole Teflon manufacturer, likes to chirp that its product makes “cleanup a breeze,” it is now becoming apparent that cleansing ourselves ofpfoa is nearly impossible.

DuPont has always known more about Teflon than it let on. Two years ago the EPA fined the company $16.5 million—the largest administrative fine in the agency’s history—for covering up decades’ worth of studies indicating that PFOA could cause health problems such as cancer, birth defects, and liver damage. The company has faced a barrage of lawsuits and embarrassing studies as well as an ongoing criminal probe from the Department of Justice over its failure to report health problems among Teflon workers. One lawsuit accuses DuPont of fouling drinking water systems and contaminating its employees with pfoa. Yet it is still manufacturing and using pfoa, and unless the EPA chooses to ban the chemical, DuPont will keep making it, unhindered, until 2015.

The Teflon era began in 1938, when a DuPont chemist experimenting with refrigerants stumbled upon what would turn out to be, as the company later boasted, “one of the world’s slipperiest substances.” DuPont registered the Teflon trademark in 1944, and the coating was soon put to work in the Manhattan Project’s A-bomb effort. But like other wartime innovations, such as nylon and pesticides, Teflon found its true calling on the home front. By the 1960s, DuPont was producing Teflon for cookware and advertising it as “a housewife’s best friend.” Today, DuPont’s annual worldwide revenues from Teflon and other products made with pfoa as a processing agent account for a full $1 billion of the company’s total revenues of $29 billion.

Teflon is not actually the brand name of a pan; it’s the name of the slippery stuff that DuPont sells to other companies. Marketers deploy the trademark as a near-mystic incantation, a mantra for warding off filth: Clorox Toilet Bowl Cleaner With Teflon® Surface Protector, Dockers Stain Defender™ With Teflon®, Blue Dolphin Sleep ‘N Play layette set “protected with Teflon fabric protector.” In one TV spot, an infant cries until Dad sets him down on a Stainmaster (with Advanced Teflon® Repel System) carpet, where baby, improbably, falls into blissful slumber. Breathing in dust from Teflon-treated rugs or upholstery as they wear down is one way we may be ingesting PFOA

. Food is another: Pizza-slice paper, microwave-popcorn bags, ice cream cartons, and other food packages are often lined with Zonyl, another DuPont brand. Technically, Zonyl does not contain pfoa, but it is made with fluorotelomer chemicals that break down into pfoa. Regardless of how it gets into our bodies, once there, pfoa stays—quietly accumulating in our tissues, for a lifetime.

Teflon is not the only nonstick, non-stain brand that has turned out to be stickier than advertised. Scotchgard and Gore-Tex, to name just two, are also made with pfoa or other perfluorochemicals (pfcs). Last year the epa hit the 3M corporation, maker of Scotchgard, with a $1.5 million penalty for failing to report pfoa and pfchealth data. Chemicals similar to pfoa have recently turned up in water supplies of suburban Minneapolis and St. Paul, near 3M facilities.

Unlike DuPont, though, 3M no longer sells pfoa: In the late 1990s, when testing blood samples for a health study, the company found pfoa even in the “clean” samples from various U.S. blood banks that it had planned to use as controls. “They realized they were contaminating the entire population,” says Richard Wiles, the Environmental Working Group’s executive director. In 2000, 3M announced that it was discontinuing pfoa production.

When 3M got out, DuPont, which until then had bought its pfoa from 3M, jumped in. Now the company’s bottom line depends on whether its product’s mythic reputation—Teflon’s own Teflon—remains intact.

So far, it seems to be holding. Nonstick pots and pans account for 70 percent of all cookware sold. “Amazingly enough, all the publicity has had no impact on sales,” says Hugh Rushing, executive vice president of the Cookware Manufacturers’ Association. “People read so much about the supposed dangers in the environment that they get a tin ear about it”—though sales of cast-iron skillets, touted as a safer alternative, have doubled in the last five years, in large part because of “the Teflon issue,” according to cast-iron manufacturer Lodge.

In fact, nonstick pans are not a major source of exposure to pfoa, because almost all of the chemical is burned off during manufacture. Still, when overheated, Teflon cookware can release trace amounts of pfoa and 14 other gases and particles, including some proven toxins and carcinogens, according to the Environmental Working Group’s review of 16 research studies over some 50 years. At 500 degrees,

→ TEFLON FUMES CAN KILL PET BIRDS ← at 660, they can cause the flulike “polymer fume fever” in humans. Even at normal cooking temperatures, two of four brands of frying pans tested in a study cosponsored by DuPont gave off trace amounts of gaseous pfoa and other perfluorated chemicals.

A $5 billion multistate class-action lawsuit representing millions of Teflon cookware owners alleges that DuPont has known for years that its coatings could turn toxic at temperatures commonly reached on the stove, but failed to tell consumers. DuPont’s website recommends not heating Teflon above 500 degrees (so it doesn’t “discolor or lose its nonstick quality”) and advises that when overheated, “nonstick cookware can emit fumes that may be harmful to birds, as can any type of cookware preheated with cooking oil, fats, margarine and butter.” But who knows how hot a pan gets, and who looks out for birds before fixing dinner? Even while researching this story, I left a nonstick skillet on the stove. The fumes smelled like fried computer, and I vowed not to do it again. But I also decided to go with the hazardous-waste flow, figuring, “We’re all toxic dumps anyway.” (ewg studies have found a “body burden” of 455 industrial pollutants, pesticides, and other chemicals in the bodies of ordinary Americans.) With toxic substances unavoidable, or at least key to convenience, we run our own self-interested cost-benefit analyses. I throw out the Teflon-coated Claiborne pants my mother-in-law sent my son, but I let him play on swing sets made of arsenic-treated wood because I don’t want to face a tantrum.

Still, consumers of Teflon pans and pants (not to mention the mascara, dental floss, and other personal care products made slippery with a touch of Tef) have it relatively safe. The people who make the stuff, and who live near the plants, face far worse dangers. The granddaddy of trouble plants—and the one inspiring a range of lawsuits—is DuPont’s plant near Parkersburg, West Virginia. Residents there have sued DuPont for polluting their drinking water with pfoa, and in March 2005, DuPont settled the case for $107 million. If an independent science panel finds links between pfoa and various health problems, DuPont will have to pay up to an additional $235 million to monitor the health of 70,000 people for years to come. Meanwhile, as part of the court order, the company is supplying the entire population of one nearby town with bottled drinking water.

The epa’s $16.5 million fine against DuPont for concealing evidence of health risks traces back to the same Parkersburg plant. According to the epa, workers were reporting health problems there for years, including birth defects in their children; as far back as 1981, DuPont scientists knew that pfoa could cross the placenta and thus contaminate fetuses. DuPont also knew that some of its workers’ babies had been born with eye defects similar to those 3M had just then reported in rats exposed to pfoa. At that point, rather than risk finding more evidence, DuPont terminated its study and didn’t report the troubling data to the epa as required by law. “Our interpretation of the reporting requirements differed from the agency’s,” the company explained in 2005.

Today, DuPont remains adamant that pfoa—whether in pots, pants, or drinking water—is no threat. The epa may say studies show unequivocally that in “laboratory animals exposed to high doses, pfoa causes liver cancer, reduced birth weight, immune suppression and developmental problems,” but DuPont’s website quotes Dr. Samuel M. Cohen of the University of Nebraska Medical Center, who says, “We can be confident that pfoa does not pose a cancer risk to humans at the low levels found in the general population.” But, notes Robert Bilott, one of the lead attorneys in the Parkersburg suit, “the general population isn’t drinking it. And they have five parts per billion in their blood. Near the West Virginia plant, it’s in the hundreds of parts per billion; and in the elderly and in children, several thousand parts per billion.”

DuPont is hardly unique in trying to cast unflattering data as incomplete or uncertain. As epidemiologist David Michaels wrote in a 2005 essay in Scientific American titled “Doubt Is Their Product,” many corporations have followed the tobacco (and more recently, global warming) model of insisting that the scientific jury is still out, “no matter how powerful the evidence.” Michaels took his title from a 1969 memo written by an executive for cigarette maker Brown & Williamson: “Doubt is our product since it is the best means of competing with the ‘body of fact’ that exists in the mind of the general public.” Even the indoor tanning industry, notes Michaels, “has been hard at work disparaging studies that have linked ultraviolet exposure with skin cancer.”

Chemical companies caught a break with the passage of the 1976 Toxic Substances Control Act (which they helped write), a measure so weak it doesn’t require industrial chemicals to be tested for toxicity. Only toxic effects, often found after a product has become ubiquitous in the environment and in people’s bodies, must be reported—and even that rule, as DuPont discovered, can be broken with only a minor hit to profits.

In the case of pfoa, it was left to the epa to finally investigate the risk to public health. That assessment, begun in 2000, is expected to go on for years. If pfoa is determined to be a proven (not merely likely) carcinogen, says agency spokeswoman Enesta Jones, “this chemical could be banned.” It would be one of theepa’s very few outright bans since 1996, when it proscribed ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons. DuPont was the world’s biggest producer of those too.

For now, DuPont is subject only to the epa’s voluntary “stewardship” program, under which it has agreed to reduce pfoa emissions from products and factories by 95 percent by 2010 and 100 percent by 2015. DuPont says it is likely to meet those deadlines: In February, the company announced it had found a new technology that reduces by 97 percent the pfoa used in making Teflon and other coatings, and it has vowed to “eliminate the need to make, buy or use pfoa by 2015.”

“It’s interesting how DuPont says they’re going to eliminate the ‘need’ to make, buy, or use pfoa,” says Rick Abraham, an environmental consultant for the United Steelworkers, which represents workers at DuPont’s plants. “It’s a self-imposed need. They need it to make money. Are they going to stockpile it, make as much as they can by 2015? Given DuPont’s history, that’s very possible. They need to make public a time frame for annual production and have it subject to third-party verification.” DuPont spokesman Dan Turner responds, “We’re going to eliminate it, period.” As for time frames, he says, “I can’t get into specifics. I can only say we’re moving as quickly as the technology allows.”

Meanwhile, DuPont has been applying a protective layer of PR to the problem. Last year, caught in a flurry of bad publicity about fines and lawsuits, the company took out full-page newspaper ads. One stated, “Teflon® Non-Stick Coating is Safe.” And, as if to flip the bird at workers’ complaints, it ran an ad in Working Woman showing a female factory worker and declaring: “DuPont employees use their skills and talents to make lives better, safer and healthier.” This year, DuPont plans to advertise its pfoa-lowering measures only in trade publications, perhaps because it’s tricky to boast of reduced pfoa while also maintaining that the chemical is harmless. “No one is better than DuPont at greenwashing,” says Joe Drexler of the Steelworkers’ DuPont Accountability Project.

Possibly. Recall DuPont’s 1990 “Ode to Joy” commercial, in which seals clapped, penguins chirped, and whales leapt to honor DuPont for using double-hull tankers to “safeguard the environment.” The seals evidently didn’t realize that a law passed after the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill required double-hull tankers. The penguins probably didn’t connect the ice melting under their flippers with DuPont’s chlorofluorocarbons either. The company fought against regulating them right up until they were banned. [Banning was not a problem, as the patent was running out. The replacement product still contains fluoride. Co2 can be used but has no market value. See end of page ]

It is in such ads that corporate fantasies and our individual ones meet and agree to ignore unpleasantries. Corporations lie to us, sure, but we make it easy for them with the little lies we tell ourselves. Especially when it comes to our everyday conveniences, it’s easier to accept the company line that there is no risk than it is to accept that authorities won’t necessarily protect us from risk. Jim Rowe, president of the union local at DuPont’s Chambers Works plants in New Jersey, told me that despite the science about birth defects among DuPont employees, many of his coworkers have convinced themselves that there’s nothing to worry about: “When we took blood tests and interviewed them, they said they were told ‘pfoa’s not a problem—it’s even in polar bears.'” Precisely. And even if DuPont (and companies that make pfoa in Europe and Asia) stopped producing and using the chemical tomorrow, the millions of pounds of it already on earth would remain in the environment and in our bodies “forever,” says the ewg’s Wiles. “By that we mean infinity.”

Denial, avoidance, and magical thinking aren’t new. Like Teflon, they’re barriers that keep unpleasant things at bay, and like Teflon, they’re entrenched deep inside us.

On average, Vermont residents have PFOA

blood levels of 10 micrograms per liter.

Scroll to top

The toxic legacy that will stick around forever.

The toxic legacy that will stick around forever.