~ Some Queensland Fluoridation History ~

Water Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not?

Timing, Circumstance, and the Nature of

The Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Act (1963)

by Harry F. Akers, Suzette A.T. Porter, & Rae Wear

Original on line document → HERE

During the last 52 years, almost all Queensland authorities have refused to implement artificial water fluoridation. Once again, the argument that ‘Queensland is different’ suggests a cultural explanation for its fluoride status. This paper argues, however, that the reason lies with the Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Act 1963 (Qld), which gives real power to the minister for Local Government, local authorities and 10 percent of electors, who can all request a referendum on fluoridation proposals. This law has given opponents of fluoridation tactical advantages, which they have used consistently.

Unlike other Australian states and mainland territories, Queensland authorities have either ignored or virtually refused to adopt artificial water fluoridation. Even though this has continued to earn the state plaudits from antifluoridationists, there has been little analysis of the reasons for Queensland’s low fluoride status.1 One possible explanation derives from the cultural hypothesis that ‘Queensland is different,’ an argument that reached its peak during the Bjelke- Petersen era and re-emerged more recently as a partial explanation for the support received in Queensland for Pauline Hanson’s One Nation (a political party).2 Proponents of this argument suggest that a range of factors, including the state’s decentralisation, comparatively low levels of education, and low levels of migration from non-English speaking backgrounds have contributed to a political culture supportive of populist and authoritarian regimes. The temptation to turn to political culture to explain Queensland’s

Health & History, 2005. 7/2 30

Water Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not? 31

fluoride status arises because many of the state’s early opponents of fluoridation inhabited the populist fringes of Queensland politics. This paper, however, argues that the reasons for Queensland’s low levels of fluoridation are more complex and lie not so much in its political culture but more specifically in the nature of state legislation governing fluoridation. The Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Act 1963 (Qld) needs to be understood in the context of the socio–political and legal circumstances preceding the time of promulgation. The Queensland fluoridation act gave and continues to give tactical advantages to antifluoridationists, which means that a great deal of political will is required to achieve fluoridation. As a consequence, successive Queensland governments have refused to revisit the legislation and local authorities have taken the path of least resistance, leaving Queensland’s largely unfluoridated status quo intact.3

The ‘Queensland difference’

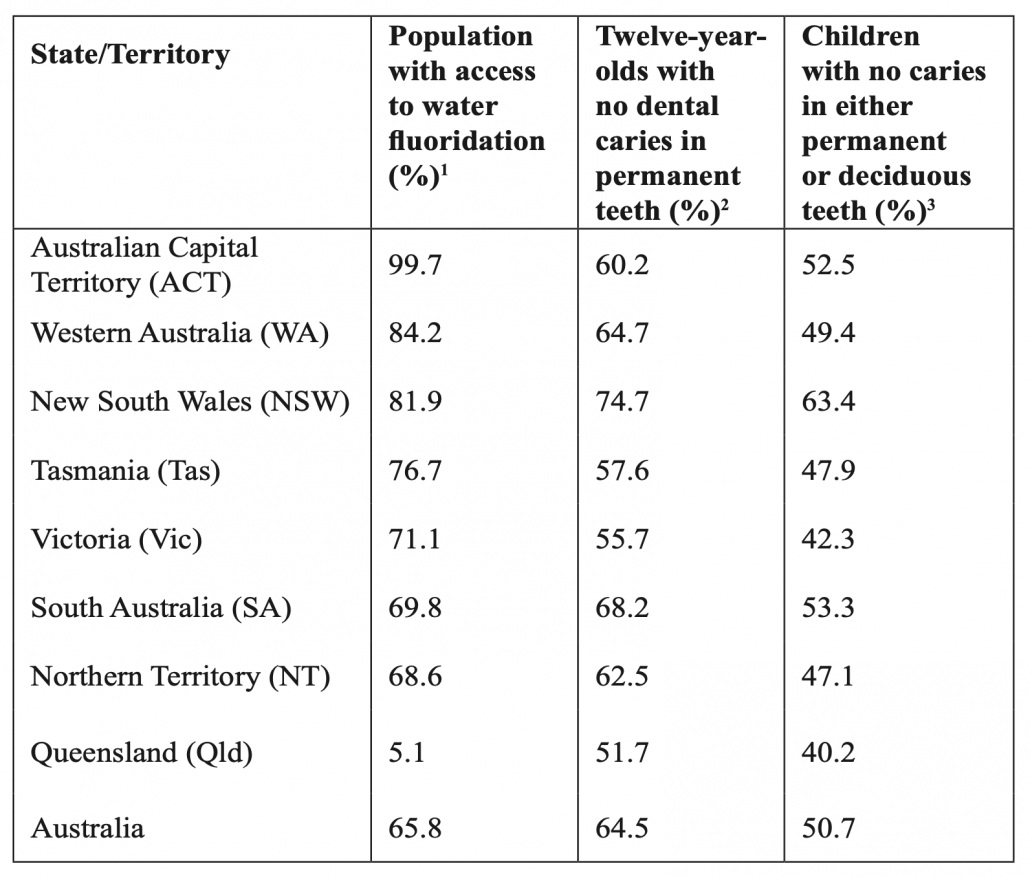

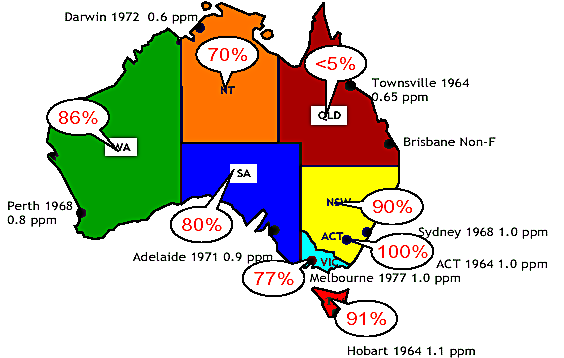

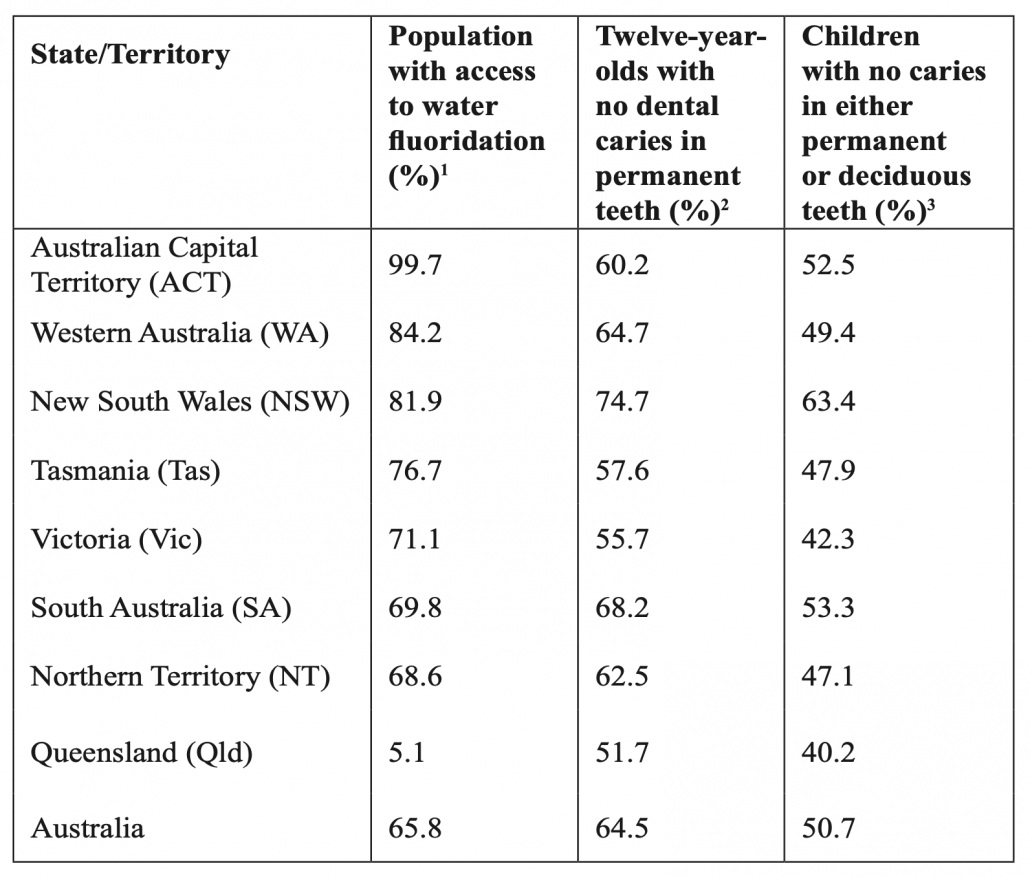

When compared with otherAustralian states and mainland territories Queensland differs in its lower proportion of the population with access to water fluoridation and with higher levels of dental caries. The Commonwealth Department of Health figures of 1984 remain largely unchanged today and demonstrate the population distribution of artificial water fluoridation,4 while Child Dental Health Surveys show, relative to other states, Queensland’s low proportion of twelve-year-old children who have never experienced dental caries (see Table 1).

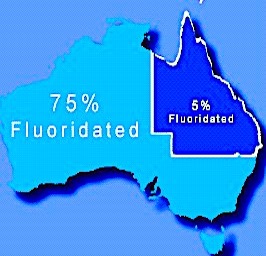

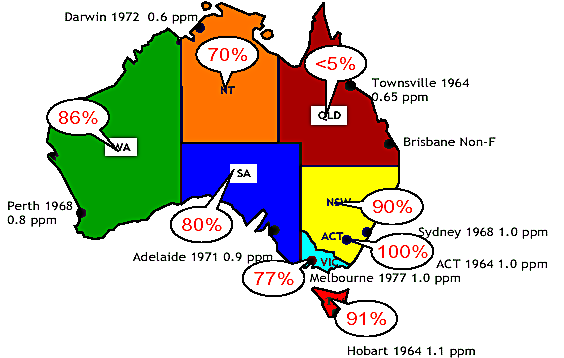

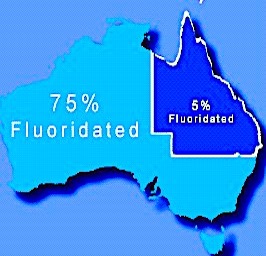

While these statistics exclude nonreticulated water supplies and home water filtration, the small percentage of Queensland’s population who imbibe artificially fluoridated water provides a stark contrast to the rest of Australia. By 1984, of the 850 Australian towns and cities that had introduced artificially fluoridated water, only seven were in Queensland.5 A recent profluoride brochure produced jointly by the Pharmacy Guild of Australia (Queensland), the Australian Medical Association (Queensland) and the Australian Dental Association (Queensland) [ADAQ] provides a perhaps even more striking illustration of the Queensland difference by showing a map of Australia with Queensland 5 percent fluoridated and the rest of Australia 75 percent (see Map 1). A more detailed representation, derived from John Spencer’s Australian dental

32 HARRY AKERS, SUZETTE PORTER, & RAE WEAR

Table 1: Artificial water fluoridation and child oral health comparisons for Australia (Source: Adapted by author from various sources—1. Commonwealth Department of Health, Fluoridation of Water: A Collection, 94; 2. Jason Armfield, Kaye Roberts-Thomson, and John Spencer, The Child Dental Health Survey—Australia 1996 (Adelaide: AIHW University of Adelaide, 1999), 24; 3. Jason Armfield, Kaye Roberts-Thomson, and John Spencer, The Child Dental Health Survey— Australia 1999: Trends across the 1990s (Adelaide: AIHW University of Adelaide, 2003), 25.)epidemiological studies, appeared in Peter Forster’s recent inquiry into Queensland Health’s systems (see Map 2). Also notable isthe fact that Brisbane is the only nonfluoridated Australian capital city. Another Queensland characteristic is the comparatively high incidence of defluoridations (the cessation of artificial fluoridation): Gold Coast (1979), Gatton Agricultural College (1979), Allora (1982), Killarney (1983), Proserpine–Whitsunday (1992), Gatton (2002), and Biloela (2003). All of these reports and statistics demonstrate Queensland’s perennial difference in fluoride status when a comparison is made with other Australian states and mainland territories.Water Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not? 33

|

|

|

|

Map 1: Fluoridation status in Queensland as compared with the rest of Australia (Source: Ingrid Tall, Kos Sclavos, and Don Anning, Healthy Teeth or Decay? Water Fluoridation: The Facts, (Brisbane: Australian Medical Association (Queensland Branch), Pharmacy Guild of Australia (Queensland Branch), and Australian Dental Association (Queensland Branch), 2003), 2.) 6 Map 2: Fluoridation status of Australian states and capital cities (Source: Peter Forster, Queensland Health Systems Review (Brisbane: The Consultancy Bureau, 2005), 53. Forster acknowledges this material as that of John Spencer.)

-

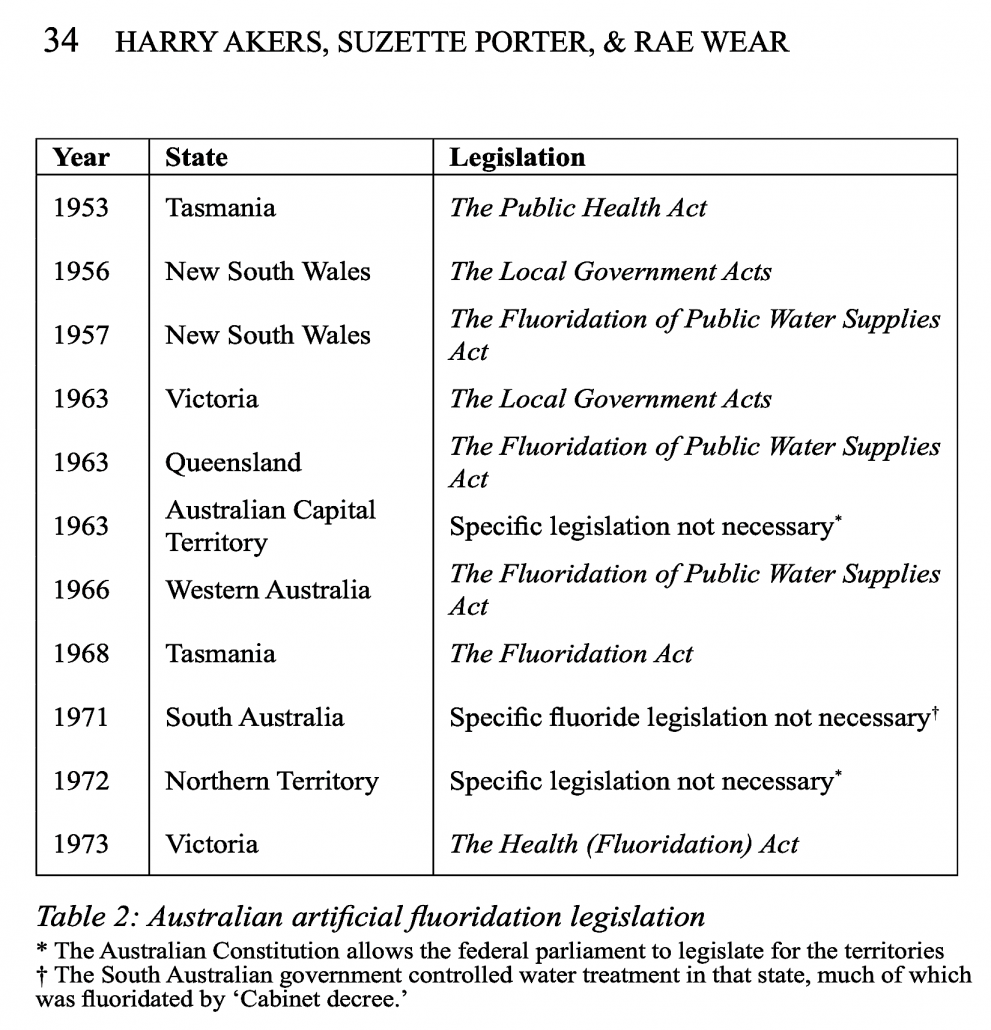

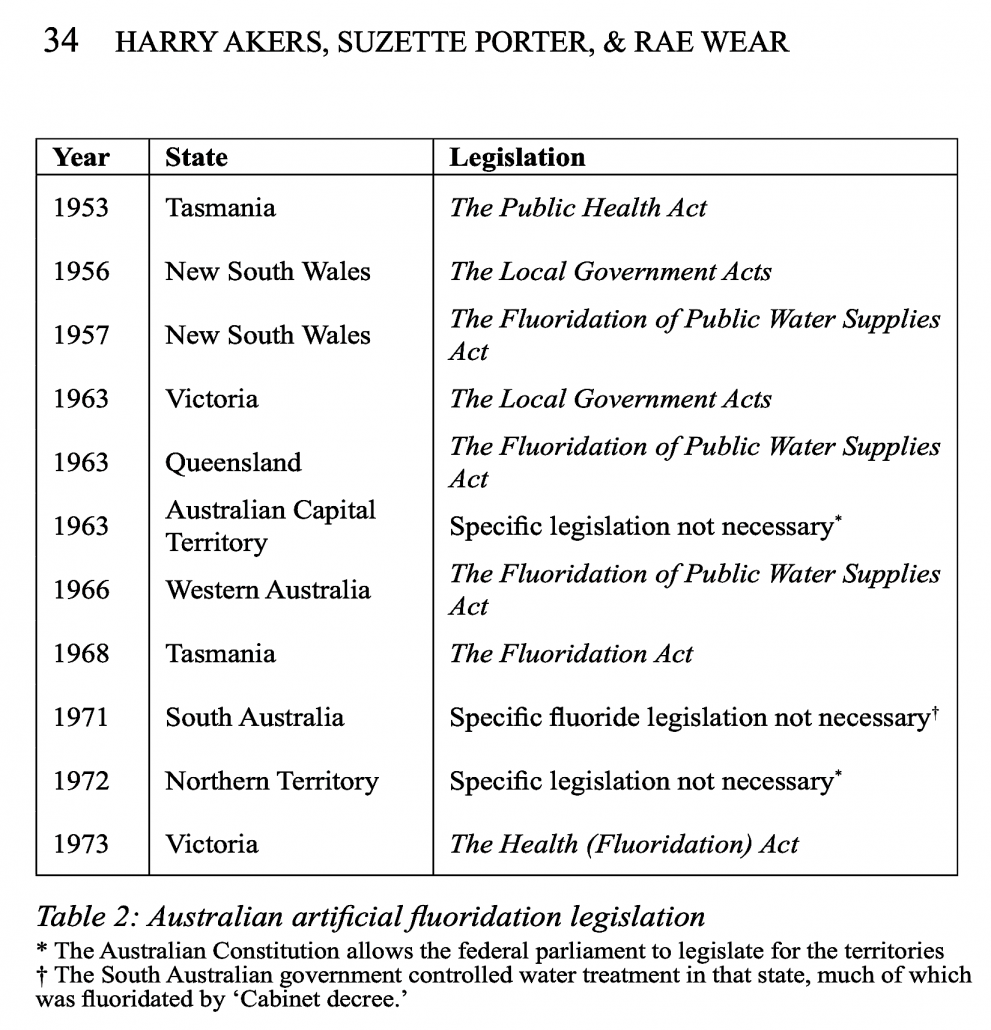

1956 New South WalesFluoride status of other Australian states and territoriesAll Australian parliaments have conducted debates over artificial water fluoridation. The arguments presented were predictable but, with the exception of Queensland, all legislatures resolved them and implemented widespread fluoridation.

-

Table 2 lists the relevant legislation used to fluoridate water in Australia.Analysis of fluoride legislation from all states and territories shows that the non-Queensland legislation all permit centralisedexecutive decisions to fluoridate and discourages the use of referenda. In addition, most of the other states provided financial incentives to fluoridate, either through the state government bearing some or all of the costs of installation or by subsidies to local authorities or water boards.The Tasmanian parliament established a centralised stateWater Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not? 35

-

authority for decision-making as a result of recommendations made by Justice Malcolm Peter Crisp, chair of an interrupted RoyalCommission (1966–1968) into fluoridation.7 Crisp did not favour the use of ‘section 61’ of The Public Health Act 1962—whichperceived fluoridation as an implied power—as the appropriate legislative vehicle for fluoridation.8 The Fluoridation Act 1968(Tas) was broadly promulgated along Crisp’s recommendations and gave the final authority to fluoridate to the health minister. The act created a personally indemnified state advisory fluoride committee, which included the director of public health, an engineer, a dentist, a medical practitioner, and a biochemist. There was no provision for local authorities to hold fluoride-related polls. A state government subsidy of 55 percent of annual costs was paid to water supply authorities.9 This legislative model led to widespread Tasmanian fluoridation because the decision-making process was centralised and enforceable.The Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Act 1957 (NSW) also concentrated power in a state fluoride committee of health andengineering experts with two additional appointments from local authorities and the minister for health. This facilitated the decision- making process. Moreover, the fluoridation act overrode any other state water act. Prior to the 1957 act, like the Tasmanian health act, the New South Wales Local Government Acts had recognised artificial fluoridation as a discretionary implied power exercised by local authorities. This was significant because, in spite of a state subsidy of 50 percent of the capital cost of installation, water boards and local authorities generally resisted the pre-1963 implementation of artificial fluoridation.10 Their opposition was overcome as a result of a strategic profluoride alliance between Dr. M.J. Flynn (an engineer and medical practitioner); Professor Noel Desmond Martin (dean of the University of Sydney Dental School); and the minister for Health, William F. Sheahan. Sheahan advocated fluoridation and, as minister for Health, had the power to appoint or remove water board members. Whether Sheahan actually threatened to ‘sack’ obstinate water board members is debatable,11 but he certainly confronted them and in one case dismissed a dissenting opinion as ‘poppycock.’12 Because of Sheahan’s pivotal role, the New South Wales legislation centralised the power to fluoridate and was backed by overt political resolve.13Victoria’s political struggle with artificial fluoridation was protracted.14 In 1954 a simple press release revealed that the ‘Health

-

36 HARRY AKERS, SUZETTE PORTER, & RAE WEARCommission’ (the Victorian Department of Health) was considering a Health and Engineering Committee’s report. Headlined by the Age as ‘Fluorine likely in water soon’, the press release claimed that the report recommended artificial fluoridation to localauthorities.15 Subsequent resistance, partly organised by Social Crediters (followers of the social and economic theories of C.H. Douglas, whose ideas were also adopted in Australia by the League of Rights) appeared in letters to the editor and signalled a longperiod of interaction between policymakers advocating fluoridation and their opponents.16 Premier Henry Bolte was ambivalent and The Public Supplies Water (Fluoridation) Bill 1964 (Vic), which delegated fluoridation to local government with a requirement of 70 percent majority at referendum for implementation, was deferred and eventually lapsed.17 This introduced ‘a period of considerable confusion’ for local authorities, which only ended in 1973 when the Victorian parliament passed The Health (Fluoridation) Act.18 This again centralised the decision-making process with an indemnified chief general manager within the Department of Health. Popular resistance continued, represented by high profile antifluoridationists such as Sir Arthur Amies, Sir Ernest Dunlop and Dr. Philip Sutton, but there was no referendum provision and Melbourne was fluoridated in 1977. Although no state subsidies were initially provided, an unspecifified capital reimbursement was approved in 1980, with plant operating costs borne by local authorities.19Because the Australian Constitution allows the federal parliament to legislate for the territories, fluoridation of the NorthernTerritory and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) was relatively straightforward. While Darwin’s fluoridation in 1972 generated comparatively little controversy, the fluoridation of Canberra was contentious.20 Nevertheless, fluoridation there was finalised by executive decision, when the federal government, acting on a recommendation from the ACT Advisory Council, autonomously fluoridated the water supply, without calling a referendum.In South Australia, the process was similarly swift and direct, beginning with the investigation of artificial fluoridation by a select committee in 1964.21 While the government took no official position in 1967,22 a year later fluoridation was endorsed.23 Fluoridated water was delivered to 888,000 residents by January 1971.24 The premier, Steele Hall, announced the decision to fluoridate in 1968 by saying: ‘The Government proposed to takeWater Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not? 37this action administratively. It would not be the subject of a Bill before Parliament.’25 He dismissed opponents’ arguments and theuse of supplements as an alternative to artificial fluoridation. In 1970 Premier Don Dunstan, who had served on the 1964 SelectCommittee, implemented the decision. Like Menzies in the ACT, Hall and Dunstan denied calls for referenda.26 Hall and Dunstanpaid a political price in that antifluoridationists challenged them in the 1970 state election but their bi-partisan resolve over thedirect government control of water processing led to the efficient implementation of fluoridation.In Western Australia The Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Act 1966 also concentrated decision-making powers. An advisory committee was established, which consisted of an indemnified commissioner of public health, two engineers, a chemical analyst, an appointed dentist, a medical practitioner, and a local government representative. This committee, still operating today, can recommend artificial fluoridation and, if the minister for Health approves, a direction for a water supply authority to fluoridate is issued.The decisions regarding fluoridation in the ACT, Western Australia, South Australia, and, later, in the Sydney-Newcastle- Hunter region (NSW) demonstrate another feature of efficient implementation: a centralised water distribution system controlled by a single authority enabling the fluoridation of many areas with a single decision. This contrasts with Queensland, which is a decentralised state where water treatment is the exclusive domain of local authority. Therefore, decisions to fluoridate are usually made on an ad hoc and site-by-site basis. In particular, in both South Australia and Western Australia, where pipeline systems distributed fluoridated water long distances, the centralised system meant that single decisions provided fluoridated water to large populations that were vastly geographically dispersed.27 At the time of the initial implementation of the fluoridation act in Western Australia, with the government controlling much of the state’s water processing, several key decisions in 1968 flfluoridated 650,000 people via the metropolitan, goldfields, and country water supplies.28Overall, the legislation from the other states and territories exhibit several features that distinguish them from the Queensland situation, particularly the diminished recourse to referenda, and the centralisation of the authority. Furthermore, in all states except Queensland, the minister for health has a direct and active role with

-

38 HARRY AKERS, SUZETTE PORTER, & RAE WEAR discretionary implementation powers because artificial fluoridation is considered to be a health issue and not a water or local authority issue. In contrast, Queensland’s fluoridation legislation has unique features that have ensured both low fluoridation levels and the continuation of fluoride debates. The repetitive and long-lasting nature of these debates is highlighted by recent media coverage,29 which was triggered by recommendations for public debate in the Queensland Health Systems Review (2005).30Background to the Queensland fluoridation actTo understand the Queensland situation it is necessary to evaluate the socio–political and legal influences on the Queensland fluoridation act. In particular, the period from 1954 (the year of Queensland’s first serious, but aborted proposal in Bundaberg) to 1963 (the year of the Queensland fluoridation legislation) requires careful examination.

-

The Chinchilla community: The legislative impetusIn Queensland, Local Government acts have general competency clauses that allow local authorities to use a discretionary powerto perform some types of duties not covered specifically by legislation. It was through this arrangement that several local waterfluoridation proposals came about prior to the introduction of the Queensland fluoridation act and influenced the course of state-wide legislation. The impetus for the state legislation can be traced to August 1958, when several local medical and dental practitioners suggested artificial water fluoridation to the Chinchilla Shire Council. After consultation with, and support from the Queensland Department of Health and Home Affairs, the shire council decided in October to fluoridate the municipal supply.31 Although there was only one dissident councilor, significant community opposition emerged when 33 percent of electors signed a petition asking for a referendum.32 ‘Section 53’ of Queensland’s Local Government Acts gave the minister for Local Government the power to call a referendum on ‘any question relating to Local Government’ when a petition was raised ‘by ten percent of electors.’33 However, without ministerial intervention, in December 1959 the Chinchilla Shire Council bowed to popular pressure and called a referendum for February 1960. This referendum campaign was highly signifificant and attracted statewide media interest. It entrenched the existingWater Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not? 39polarisation of supporters and opponents, and elicited public ministerial and departmental assurances that there would be neithercompulsion nor secrecy associated with Queensland fluoridation proposals.34 Fluoride advocates included Dr. D.W. Johnson, the deputy director-general of Health; Dr. H.W. Noble, Liberal minister for Health and Home Affairs (1957-64); ADAQ; the Queensland Health Education Council; Dr. Felix Dittmer, Australian Labor Party (ALP) senator and former deputy-leader of the parliamentary wing of the Queensland ALP; and local supporters who all confidently endorsed artificial water fluoridation.35 This alliance faced the state’s foremost antifluoridationists, J.E. Harding, A.E. Webb, and R. Bromiley of the Rockhampton Anti-Fluoridation Association.36 Harding and Webb had a long association with Social Credit and the League of Rights via rural action groups, various political parties and the Rockhampton Monetary Reform League.37 All three were drawn to conspiracy theories and were advocates of direct democracy devices such as referenda.38The resounding 937 to 341 re�ection of flfl fluoridation at Chinchilla, portrayed by one state newspaper as representing the ‘mirror of Queensland,’ reinforced the right to the referendum mechanism as a means of resolving whether or not to implementfluoridation proposals.39 On the day of the referendum the Courier– Mail made its opposition to ‘involuntary’ fluoridation clear when it editorialised: ‘To propose dosing whole communities at the turn of their taps has a well-intentioned but uneasy, foretaste of “Big Brother” dictatorship.’40 As well as bolstering the popular perception of a right to referenda, the Chinchilla result also signalled that local governments rather than the Health Department were the relevant authority regarding fluoridation proposals. Dr. Noble announced that the ‘Health Department would not initiate any further moves for fluoridation by a local authority. Department policy was to let a local authority decide for itself whether it wanted to use fluorine.’41 In addition he made it clear that the state government wanted such decisions to be open in order to forestall any allegations of secrecy regarding fluoridation.42 This was good news for Social Creditors, the League of Rights, and other antifluoridationist forces for whom the rights to petition and to referenda were fundamental.43 These groups either created, or capitalised on, a view that referenda were integral to any fluoridation proposal and began to label independent local authority fluoridation without referenda as undemocratic. Eventually they broke the Queensland fluoride debates into two40 HARRY AKERS, SUZETTE PORTER, & RAE WEAR issues: referenda and fluoridation per se.44Biloela township: The legislative triggerThe fluoride focus turned to Biloela, where on 15 July 1960 the Banana Shire Council decided to fluoridate Biloela’s communalwater supply to a ‘strength recommended by the Department of Local Government.’45 The Banana Shire Council, supported by the Callide Valley Progress Association, was prepared to go ahead and fluoridate without a referendum.46 Unlike Chinchilla Shire Council, Banana showed lasting resolve, perhaps because they faced less resistance given that there were two conflicting petitions: the 1960 petition was of 494 signatures and endorsed fluoridation, while the 1962 petition was of 485 signatures and called for a referendum.47 In 1964, Banana Shire Council in a six-to-five vote relented in the face of public pressure and called a referendum, which involved postal voting by Biloela township residents on the state electoral roll.48 The 523 to 471 result endorsed fluoridation, which was eventually implemented.49Although this moves us beyond our period of examination, the response to the referendum result, punctuating the vigorous public debate throughout the lead-up to the 1963 Queensland legislation, is worth mentioning. The Rockhampton Anti-Fluoridation Group, the Anti-Fluoridation Council of Australia and New Zealand, and the Biloela Pure Water Committee publicly challenged the result on the grounds that ratepayer’s money was used to promote fluoridation and that the Council had disenfranchised some shire residents who lived outside Biloela township.50 The antifluoridationists further argued that the restricted referendum was unprecedented, that the result should be declared ‘null and void,’ and that the Banana Shire Council did not have the moral right to fluoridate.51 In all, the Biloela controversy lasted five years and was widely reported. Media coverage included allegations of defamation, complaints about fictitious nom de plume correspondents, claims of untrue statements about the council’s role, and concerns over litigation. On 4 February 1963 the Rockhampton Anti-Fluoridation Group threatened an in�unction to stop imminent fluoridation at Biloela.52The public debate masked serious problems for Queensland’s solicitor-general and the parliamentary draftsman. Although not publicly acknowledged, advice from the solicitor-general, W.E. Ryan, revealed that the minister for Local Government had considered intervention to order the Banana Shire CouncilWater Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not? 41 to conduct a referendum.53 Of further concern were the issues of legality and indemnity. Ryan’s advice to the director of Local Government continued:I am of the opinion that the Minister has a wide power to refer questions relating to local government for the opinion of the electors, that he has a discretion as to whether or not to direct a poll, that if he directs the poll be taken the local authority must take it and that, in particular, he has the power to direct the poll on fluoridation if he so desires, provided it is a matter for local government. Another question, however, which might arise is whether the local authority itself has the power to carry into effect a scheme of fluoridation in the water supply for the purpose of preventing dental decay …The power of the Council to introduce fluorine into water could easily be the subject of litigation and this would be particularly so if a person claiming to be in�ured by the fluoridation brings an action against the Council for injuries sustained … It is a moot point whether fluoridation is a matter for local government … In my opinion, if the Banana Shire Council proceeds with its scheme it may have to run the risk of litigation. The carrying of a poll would not improve its legal position. … There is a power to make regulations under Section 33 (xi) of the Health Acts, 1937 to 1962…. I understand that the power has not been used and it would not appear to cover fluoridation. 54 Ryan clearly doubted that fluoridation was a function of Queensland’s local government even though general competency clauses of The Local Government Acts had been used in New South Wales (Yass, 1956). Furthermore, even though the public health acts were used in Tasmania (Beaconsfield, 1953), Ryan felt they were inappropriate for Queensland. In Ryan’s opinion, these interstate examples could not be used as precedents in Queensland law and litigation was a real threat. His advice went further. He also informed the director of Local Government that he ‘understood’ that fluoridation of communal water supply was ‘mass medication.’ In early July, the parliamentary draftsman, J. Seymour, advised Dr. Noble that he agreed with Ryan’s advice.55 This was out of step with the findings of the 1957 New Zealand ‘Commission of Inquiry’ into fluoridation, findings in North American courts and the general argument put forward by profluoridationists.5642 HARRY AKERS, SUZETTE PORTER, & RAE WEARFurther legal concernsIn addition to the concerns raised by Ryan and Seymour, there were a number of contemporaneous unresolved legal issues that impacted on the parliamentary debates preceding the implementation of the Queensland fluoridation act. Several New Zealand antifluoridationists challenged ‘section 240’ of The Municipal Corporations Act 1954 (NZ) through the New Zealand legal system, which led to the issues being referred to the Privy Council.57 This legislation empowered a water corporation to construct waterworks for the supply of ‘pure water’ for the inhabitants, and antifluoridationists argued, among other things, that the addition of fluoride was a breach of the municipal corporations act because water was no longer pure. In essence, the case involved a defifinition of ‘pure water’ and the alleged use of fluoridated water as a ‘medicine.’58 While the judgment eventually endorsed the legality of fluoridation in the highest court within the Commonwealth, these issues were unresolved at the time of the Queensland parliamentary debates.Furthermore, on 29 August 1963, several weeks after the initiation of the Queensland drafting, C.A. Kelberg, a ratepayer of the City of Sale (Victoria), which had decided to fluoridate, issued a writ against the fluoride equipment manufacturer, Wallace and Tiernan Pty Ltd. Kelberg lodged an injunction restraining the corporation on the basis of its alleged intention to fluoridate a reticulated water supply.59 Kelberg also challenged the statutory authority of the City of Sale to fluoridate under ‘section 232’ ofThe Local Government Act 1958 (Vic). This action, which eventually resulted in a temporary successful injunction on a technicality of incorrect by-law use, was also current during the drafting of the Queensland legislation. There were several other important legal challenges involving personal liberty in Ireland and the United States of America.60Parliamentary concerns about fluoridation were further heightened when a letter implicating fluoride in adverse effects on cell growth appeared in the British Medical Journal of 26 October 1963. It was well publicised and considered sufficiently importantfor the National Health and Medical Research Council to quickly issue an edict endorsing the safety of fluoridation.61 Dr. Nobletemporarily withdrew the Queensland bill from its first reading while inquiries and assurances were sought from researchers andscientific advisors.62Water Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not? 43 Queensland was not the only state to have difficulty in framing legislation to accommodate water fluoridation and did not conductits debates in isolation. In Western Australia the Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Bill 1963 passed the Legislative Assembly but was defeated in the Legislative Council with a tied vote.63 Further acrimony emerged in the ACT when Gordon Freeth, minister for the Interior, announced that the Menzies’ federal government would agree to an ACT Advisory Council proposal to fluoridate Canberra without a referendum.64 Throughout 1962–64, fluoridation also had been contentious in New South Wales where implementation had been tardy. Matters came to a head when the recalcitrant Sydney and Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board announced in May 1963 that it would not fluoridate Sydney’s water supply in spite of strong support for the measure by Health Minister W.F. Sheahan and Premier Robert Heffron (1959–64).65 On 28 January 1964 Heffron ordered the Sydney Metropolitan Water Board to fluoridate.66 Against this background of doubt and debate, the Queensland government framed its legislation.The emergence of the Queensland fluoridation actIt appears that the Queensland government decided to legislate on water fluoridation because of concerns regarding issues of legality, litigation and compulsion, rather than dental health. There is no evidence to implicate fluoridation as an issue in the June 1963 Queensland election, which comfortably returned a Liberal– Country Party coalition.67 Parliamentary concern over dental health also appeared to be minimal: one state parliamentarian claimed to be none the worse for his dentures; two parliamentarians who were also dental technicians, opposed fluoridation; Dr. Noble was the only ministerial participant in the debate and no Country Party member contributed.68 In a conscience vote, only forty-seven from seventy-eight parliamentarians and seven out of thirteen ministers voted, and the minister for Local Government, the state’s key figure on the matter of fluoridation, did not vote. This was an era when the general population accepted dental decay as normal and inevitable. Nevertheless, the Queensland government decided to draft legislation about a month after the election, without the benefit44 HARRY AKERS, SUZETTE PORTER, & RAE WEAR of advice from a Royal Commission, Select Committee or independent review. Documentation of communication between local and state governments suggests that the main trigger was the impending independent fluoridation of Biloela, Townsville and possibly Mareeba.69 Cabinet had firm requests from the first two to allow local authorities to add fluorine to a water supply and to guarantee indemnity for a local authority providing it obeyed statutory safeguards.70 The parliamentary draftsman’s initial advice in July 1963, stated:The object of the Bill which I suggested for consideration was to strengthen the position of those local authorities which proposed to introduce fluorine to the water against a person who might be minded to commence legal proceedings claiming that he suffered an injury thereby.71Dr. Noble’s submission to Cabinet suggests a similar desire to avoid litigation from antifluoridationists:It [water fluoridation] has been accepted by the medical and dental profession … It is a big factor in the prevention of dental caries even though not the total answer … a vociferous though small group, who without any scientific facts to support them, oppose fluoridation … A member of this group might be minded to commence legal action against a Local Authority … The Solicitor- General states it is a moot point whether fluoridation is a matterfor Local Government, and the power to make Regulations under Section 33 (xi) of the Health Acts 1937–62 does not appear to cover fluoridation.72In the ‘initiation in committee’ phase, he further spelt out the purpose of the Bill:It is desirable that a Bill be introduced relating to the addition of fluorine to public water supplies. … To make legal the addition of fluorine. … To indemnify any local authority against … legal action. … It does not coerce local authorities in any way … The local authority must follow certain procedures … The present system was open … to legal challenge.73Despite Dr. Noble’s concern about litigation, the 1963 legislation failed to fully address the indemnity issue. This came to constitute a de facto escape clause for those not wanting to become embroiled in Water Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not? 45 debates about fluoridation, including successive state governments. In spite of recommendations in 1972 and 1974 from two ministers for health, the government refused to revisit the Queensland legislation.74The matter of indemnity was in fact extremely prominent in the pre-1964 fluoridation debate in Queensland. While we havealready touched on—through a brief look at the development of fluoridation legislation in other states—the roles of several other key factors in causing significantly lower artificial fluoridation levels for Queenslanders compared with other Australians, indemnity, too, must be considered in this light. Through a more in-depth examination of some of these issues, we can begin to understand that a great deal of determination is required in order to impose artificial water fluoridation in Queensland because of the tactical advantages used assiduously by the antifluoridationists.IndemnityDuring the drafting of the Queensland legislation indemnity was a very sensitive issue, a fact reflected in a 1964 advisory—distributed to all local authorities—which explained that the Queensland fluoridation act and its Regulations must be fully observed if the indemnity provisions were to apply.75 Furthermore, the indemnity applied only to ‘costs and expenses’ and did not cover damages.76 This issue was raised in The Brisbane Lord Mayor’s Task Force on Fluoridation Report (1997) and at the time the Local Government Association of Queensland’s legal advice re-affirmed the 1964 view and added that the ordinary principles of negligence applied.77 In a litigious action, ‘the State Treasurer has to be satisfied that the alleged cause of action or other proceeding created no legal liability whatsoever in local government.’78 This gave the state government a loophole that may have left a local authority liable for damages if a resident proved in�ury resulting from the addition of fluoride to a reticulated supply.There were three further indemnity issues that the legislation failed to address. The first was the paradoxical fact that the Queensland fluoridation legislation ignored the special Queensland circumstance involving those potable water supplies such asBarcaldine and Julia Creek, which are naturally over fluoridated. Artesian fluoride was a significant and widespread concern in rural46 HARRY AKERS, SUZETTE PORTER, & RAE WEARcommunities in north-western and central-western Queensland.79 Excessively high and long-term consumption of high artesian fluoride affected humans and animals, yet the Queensland fluoridation act and its indemnity only applied to artificial fluoridation. There would be no forced defluoridation of reticulated artesian supply within Queensland.80The second issue involved Queensland’s failure to fluoridate, which meant that fluoride supplements (tablets or drops) became the recommendation of local authority. From a biological perspective, these are poor alternatives in caries prevention. Furthermore they could only be dispensed via special licence or through a pharmacy, and distribution by local authority was illegal until a 1966 amendment of the regulations.81 In 1997 the indemnity issue surfaced when ADAQ argued that a local authority’s refusal to fluoridate, together with its support for supplements, meant that it could be legally responsible for dental fluorosis resulting fromsupplement ingestion.82 These problems reflect a serious legislative omission, specific to Queensland, in the failure to establish astatutory board or commission for authoritative consultation about the complexities of fluoride-related matters.Lastly, a decision to accept risk without indemnity cover may be taken by local government if the perceived risk is low and theeconomic benefit high. In Queensland the annual budget for state dental care is over $120 million and even a small reduction in dental caries could provide significant savings.83 However, the paradox is that the benefit of water fluoridation as reduced dental caries would be reflected in savings to state government, leaving local authority with both the cost of implementation and the risk of litigation but without the possibility of economic gain. It was therefore often easier for local authorities to ignore the issue altogether rather than to attempt fluoridation.Local government responsibilityThe relationship between the Queensland fluoridation act and The Local Government Acts is peculiar to that state and, while itwas politically convenient, it also reflected local government’s responsibility for reticulated supply.84 In 1964, Queensland hadneither water boards nor state responsibility for water processing. Water processing is still a local government matter today and the aforementioned legislative linkage gives local authorities a Water Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not? 47 discretionary power to fluoridate, but simultaneously restricts this right by establishing three levels of intervention involving (a) the minister for Local Government’s power to order a referendum if he/she perceives popular opposition, (b) local authority’s ability to call a referendum if so desired, and (c) the popular right to referendum if a 10 percent elector petition is raised. Hence, unlike other Australian states and mainland territories, local governments have largely retained their authority on fluoride-related matters, but could be forced to hold a referendum by ministerial direction or elector petition. Alternatively it might opt to initiate a referendum itself in order to ‘de-politicise’ the surrounding debate.Unlike other Australian states where the minister for Health is the minister responsible for fluoridation, in Queensland theminister for Local Government exercises this role, albeit by intervening to order that a referendum be held.85 Dental health, however, has traditionally not been a local authority responsib

ility and state funding for fluoridation has been inadequate. There isno state subsidy to defray annual operating costs, and prior to the Queensland fluoridation legislation, Dr. Noble had reduced the plant installation subsidy from 50 to 25 percent.86 The issue of subsidy surfaced again in Queensland with the defluoridation at Biloela in 2003. Banana Shire Council’s chief executive, John Hooper, said: ‘This decision was made because the cost to upgrade the treatment facility to meet the requirements of workplace health and safety and the code of practice for fluoridation of water supplies … is estimated … in the vicinity of $80,000.’87 The financial implications of fluoridation arose again in 2005 with Premier Peter Beattie’s offer of six million dollars to local authorities for fluoridation. The offer was described as a ‘sick joke’ by the Local Government Association of Queensland (LGAQ) chief executive who estimated the real cost at $56.5 million,88 and who, within days, teamed up with the provincial mayors in resorting to the perennial Queensland tactic: a call for a referendum.89 To this day, fluoride campaigns are conducted under the auspices of a local government structure that is under-resourced and which has no constitutional responsibility for dental health.Differing political and bureaucratic perspectives at state level have intensified these difficulties with local authorities. While various Queensland ministers for Health promoted artificial water fluoridation, they were virtually irrelevant in its implementationbecause they were subservient to the right to referendum either at48 HARRY AKERS, SUZETTE PORTER, & RAE WEARthe behest of the minister for Local Government, local authority, or the ratepayers. This division was exacerbated in the yearsbetween the introduction of legislation in 1963 and 1983, because the Liberal party controlled the Health portfolio and the Country (later National) Party controlled the Local Government portfolio. For example, Dr. Llewellyn Edwards (Liberal health minister, 1974–78) was a fluoride advocate, while Russell Hinz�e (minister for Local Government, 1974–87) opposed it.90 As chairman of Albert Shire Council, Hinze had been quoted in a local newspaper as saying: ‘Don’t you think we have enough problems without introducing fluoridation? You know it is a very controversial matter.’91 The article continued, ‘The fluoridation cranks in USA and Mudgeeraba know little about this chemical. The greatest authority on Fluoridation in Australia, Mr. E.J. [sic] Harding, says the boost for the wonder chemical is so much ballyhoo.’ Voices like Harding’s opposing fluoridation and seeking petition were raised whenever referenda were called.ReferendaLocal Government ministers have irregularly exercised discretionary powers of intervention but when they have ordered a referendum the fluoridation proposal has almost always been defeated. The exceptions—fluoridation without recourse to referenda—indicate a reluctance to engage in referendum when officials are determined to fluoridate, suggesting an awareness of the almost unfaltering success of antifluoridationists in the case of a referendum. For example, ministerial authority was not exercised against Mareeba Shire Council when it fluoridated in 1966, nor in 1971 when the American-based mining company, Utah Development Company Limited, proposed to fluoridate the reticulated water supply of Moranbah, the local town for an anticipated mining development. In this instance, state cabinet endorsed fluoridation without controversy, ministerial intervention, or referendum.92 However when Gympie City Council announced fluoridation in 1970, the minister for Local Government intervened and ordered a referendum, which resoundingly defeated the council’s proposal.93 Although results were not centrally recorded, official referenda have also been conducted at the following locations: Allora, Ayr, Biloela, Chinchilla, Eacham Shire, Emerald, Mackay, Redcliffe, and Stanthorpe.94 Only Biloela and Allora were successful forWater Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not? 49 fluoride protagonists, with the other local authorities invariably having a heavy ma�ority against fluoridation.The virtual institutionalisation of referenda advantages antifluoridationists who marshal themselves over the issues of both direct democracy and water fluoridation. This was effectively demonstrated in July 1964 when the state government targeted seven ma�or local authorities for regional fluoridation seminars. The aim was to educate local authority about the merits of fluoridationbut on the eve of the seminars, six mayors publicly announced that they were committed to referenda as the means of finalarbitration.95 Once a referendum is announced, antifluoridationists from both Queensland and interstate begin campaigning, sewing sufficient seeds of doubt for fluoridation to be defeated. Typically their arguments focus on safety concerns, costs, individual liberty, and direct democracy.In 1953 Professor Arthur Amies and Dr. Paul Pincus first articulated safety concerns about artificial water fluoridation inAustralia.96 As dean of the Melbourne Dental School, Amies was influential within and outside the dental profession. He based his opposition on the potential cumulative toxicity of fluoride, vagaries in daily intake, and disquiet about methodology within the North American field studies. Amies’ views were broadly circulated. In 1959 a senior research fellow of the University of Melbourne, Dr. Philip Sutton, published his monograph, Fluoridation: Errors and Omissions in Experimental Trials, which endorsed and refined Amies’ concerns. 97 Fluoride advocates contested Sutton’s thesis but the ‘controversy’ appeared in a Courier–Mail editorial on the day of the Chinchilla referendum.98 After 1980 a new generation of Australian antifluoridationists re�uvenated Sutton’s thesis. Dr. Mark Diesendorf challenged the ethics of fluoridation, the methodology within some British and Australian trials, and he also highlighted the decline in caries in nonfluoridated areas.99Local government also complained about the cost of fluoridation and the inefficiencies involved in treating total water supplies.This view was recently expressed by Mark Girard, executive officer of the Queensland Water Directorate: ‘Only one percent ofthe water consumed by households is used for drinking purposes and, given the total life cycle costs, there may be more efficient ways of delivering fluoride to the community than via the water supply.’100 The Gatton Shire Council, based on a semi-rural area where some reticulated water is used for irrigation purposes, put50 HARRY AKERS, SUZETTE PORTER, & RAE WEARsimilar arguments forward when it defluoridated in 2002.101 At a more political level, antifluoride groups targeted politicians and communities via newsletters and pamphlets. This correspondence invariably dwelt upon themes of compulsion and safety, but often of inferred subversion. The more conspiratorial amongst them provide perfect examples of the paranoid style of politics that in the past has led to accusations of ‘Queensland difference.’102 For example, one Queensland antifluoridationist, D.W. de Louth, signed off his newsletters with a quote from the‘Protocols of Zion’ and the statement ‘Fluoridation is Jewish.’103 Harding’s conspiracy theories embraced alleged Zionist control of international monetary and political systems and he regularly described fluoridation as a poison that led to ‘the slavery of

massmedication.’104 Whilst the claims by antifluoridationists published in scientificjournals are debated and counter-debated,105 the process has created uncertainty in the minds of the public. A monitoring of talk-back radio broadcasts about water fluoridation since 1997 indicated two major public concerns: the debate among ‘experts’ (seenas uncertainty in scientific opinion) and the issue of individual autonomy versus compulsion in deciding what is added to water.106However, several opinion polls taken since 1996 suggest that the public approval of water fluoridation in Brisbane has exceeded 50 percent.107 A 2005 LGAQ report involving a phone survey of four hundred Queenslanders found ‘73% of those expressing a view in favour,’ but LGAQ president, Cr. Paul Bell, argues that this has to be balanced with ‘almost 70% would like to see a state-wide referendum first.’108ConclusionReferenda in Queensland are almost always defeated because the arguments against it sow seeds of doubt in the minds of many voters. The activities of antifluoridationists and the conspiratorial nature of some of their arguments are a reminder of the old arguments about ‘Queensland difference.’ Queensland’s low levels of fluoridation cannot, however, be blamed directly on the state’s political culture. Rather, they are a function of the legislation that fails fully to address concerns about litigation and gives responsibility for fluoridation to local government rather than the health minister. Furthermore, past experience has created the expectation that theWater Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not? 51public will always have the opportunity to vote on fluoridation proposals via a referendum. The Queensland legislation has placedwater fluoridation proposals into an inter-governmental and inter- departmental impasse, which is where many politicians prefercontroversial issues to lie. Few want to risk pushing fluoridation in the face of vocal and well-organised opposition. Nor do theywant to risk the possibility of litigation by antifluoridationists who have used the scope given to them by the state’s legislation to advantage. Further, by delegating water fluoridation to local authorities, the Queensland legislation leaves this responsibility to a tier of government that is unprepared, under-resourced, and unconvinced that fluoridation is worth the trouble.University of Queensland1. Ross Fitzgerald, “Trading Tooth Decay for Cancer,” Australian, 26 May 2005, 11; Jim Soorley, “Soorley on Sunday: Listen to the Learned Professor,” Sunday Mail, 30 October 2005, 23.2. Murray Goot, “Hanson’s Heartland Who’s for One Nation and Why?” in Two Nations, edited by Robert Manne (Melbourne: Beckman Press, 1998), 51–73.3. This study used traditional historical research methods involving documents from the Australian Dental Association Queensland Branch, Queensland State Archives and theUniversity of Queensland Dental School. Microfilm material came from the University of Queensland Fryer Memorial, John Oxley, and Bundaberg Municipal Libraries.4. Commonwealth Department of Health, Fluoridation of Water: A Fluoridation of Water: A Collection and Statements (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service,1985), 94; Ingrid Tall, Kos Sclavos, and Don Anning, Healthy Teeth or Decay? Water Fluoridation: The Facts, (Brisbane: Australian Medical Association (Queensland Branch), Pharmacy Guild of Australia (Queensland Branch), and Australian Dental Association (Queensland Branch), 2003), 2.5. Commonwealth Department of Health, Fluoridation of Water: A Collection, 9; Commonwealth Department of Health, Fluoridation of Water in Australia 1984 (Canberra:Australian Government Publishing Service, 1985), 13.6. For a prior version, see Australian Dental Association Queensland Branch, There Shouldn’t be any Boundaries … to Healthy Teeth (Brisbane: Australian Dental Association Queensland Branch, 1997), 1.7, Peter Crisp, Report of the Royal Commissioner into the Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies (Hobart: Tasmanian Parliament-Government Printer, 1968), 1–265.8. Ibid., 231–4, 239.9. Peter Barnard, “Communities Fluoridated in Australia, 1968,” Australian Dental Journal 14, no. 6 (1969): 393.10. Ibid.,392,394.Barnard’sfiguresforNSWconfirmapre-1963hesitancetofluoridate, although he does not state this in his paper.11. See Wendy Varney, Fluoride in Australia: A Case to Answer (Sydney: Hale and Ironmonger, 1986), 121. While Varney acknowledges that evidence about threats of ‘sacking’ is inconclusive, we concur that Sheahan had that power and that relations with52 HARRY AKERS, SUZETTE PORTER, & RAE WEAR some board members were strained. 12. Western Australia Legislative Assembly, Debates 165 (1963), 1450. 13. Ibid., 1449–50; “Board Member Urges Decision on Fluoride by State,” SydneyMorning Herald, 31 May 1963, 1. 14. Brian Head, “The Fluoridation Controversy in Victoria: Public Policy and GroupPolitics,” Australian Journal of Public Administration XXXVII, no. 3 (1978): 257–73. 15. “Fluorine Likely in Water Soon,” Age, 6 November 1954, 12. 16. H. Hill, “Fluorine in Water Supply,” Age, 27 November 1954, 2; H. Gerrand,“Fluorine in Water Supply,” Age, 27 December 1954, 2; Head, 262–3. 17. Ibid., 264. 18. M. Myers, V. Plueckhahn, and A. Rees, Report of the Committee of Inquiry into theFluoridation of Victorian Water Supplies for 1979–80 (Melbourne: Legislative Assembly (Victoria), 1980), 70.19. Ibid., 72.20. Commonwealth, House of Representatives, Debates 40 (1963), 1161–71; Commonwealth, House of Representatives, Debates 41 (1964), 1139–55.21. The Select Committee of the House of Assembly, Report of the Select Committee of the House of Assembly on the Fluoridation of Water Supplies (Adelaide: The SouthAustralian House of Assembly, 1964), 1–61.22. South Australia Legislative Council, Debates 3 (1967), 2573. 23. “Fluoride ‘Where Practical,’” Advertiser, 1 August 1968, 3. 24. “Fluoride Comes to Adelaide,” Advertiser, 29 January 1971, 1. 25. “Adelaide Water to be Fluoridated,” Advertiser, 31 July 1968, 1. 26. “No Fluoride Referendum,” Advertiser, 15 August 1968, 11.27. Barnard, 393–4.28. Dudley Snow, The Progress of Public Health in Western Australia 1829–1977 (Perth: Public Health Department, 1981), 125; Barnard, 394.29. “Not ‘Guinea Pigs’ on Fluoridation,” News–Mail, 5 November 1954, 2; “No Fluoridation without Vote,” News–Mail, 8 December 1954, np; “Dental Association Reply to Water Fluoridation Letter,” News–Mail, 22 December 1954, n

p; John Evans, “Editorial: Fluoridation, to Be or Not to Be,” Bugle, 21 October 2005, 4; Spencer Gear, “Anti-Fluoride Case Stated,” News–Mail, 1 November 2005, 6.30. Forster, 54, 155.31. “What Will be the Impact of Saturday’s Poll?,” Chinchilla News, 18 February 1960, 1; “Bars Secrecy in Fluoridation Govt States Why,” Courier–Mail, 16 February 1960, 9.32. JackHarding,“TheFluoridationBattleinAustralia,”1961,JackHardingCollection, Box 10, University of Queensland Fryer Memorial Library File UQFL265 (hereafter UQFL265), Brisbane, 2.33. W. Ryan, “Written Communication to the Director of Local Government,” 25 February 1963, in author’s possession.34. “Bars Secrecy in Fluoridation Govt States Why,” Courier–Mail, 16 February 1960, 9; “State Denial on Secret Fluoridation,” Morning Bulletin, 16 February 1960, 15.35. “Fluoridation Vote: Minister for Health Has Faith in People’s Commonsense,” Chinchilla News, 11 February 1960, 4; “Deputy Health Director for Fluoride,” Morning Bulletin, 6 February 1960, np; A Robertson, “Fluoride Question: ALP Not Implicated Says President,” Chinchilla News, 28 January 1960, 1.36. “Chinchilla Pre-Poll Drive Team to Combat Fluoridation Plan,” Courier–Mail, 9 February 1960, 5.37. The Monetary Reform League, “Minute Book No.3 Rockhampton, 1946–1950,” Jack Harding Collection, Box 4, UQFL265; Jack Harding, “Written Communication to E.D. Butler, 28 April 1960,” Jack Harding Collection, Box 4, UQFL265.38. Jack Harding and Ralph Bromiley, “Warning Sodium Fluoride is a Deadly Poison Similar to Arsenic,” (Rockhampton: The Anti-Fluoridation Association, 1960), 1–2; TedWebb, “Fluoridation,” Morning Bulletin, 7 May 1964, np.39. “State Denial on Secret Fluoridation,” Morning Bulletin, 16 February 1960, 15; “Fluoridation Vote Chinchilla Says ‘No’ – Definitely,” Sunday Mail, 14 February 1960, 1;

Water Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not? 53

“Chinchilla’s ‘No’ to Dental Plans!” Truth, 14 February 1960, 3. 40. “In Your Water,” Courier–Mail, 13 February 1960, 1. 41. “State Denial on Secret Fluoridation,” Morning Bulletin, 16 February 1960, 15. 42. “Bars Secrecy in Fluoridation Govt States Why,” Courier–Mail, 16 February 1960, 9. 43. Mira Louise, Fluoridation the Poisoner (Adelaide: Shipping Newspaper (SA)

Ltd, 1954), 1; Rockhampton Anti-Fluoridation Association, “Minute Book 1956–1968 Rockhampton,” 1968, Jack Harding Collection, Box 22, UQFL265; Australian League of Rights, Fluoridation (Melbourne: Australian League of Rights, no date), 1–2. A similar pamphlet was found in Queensland State Archives (hereafter QSA), stamped 15 July 1964: Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Batch Files, Series SRS 1043�1, no. 633: part 1, Box 1036, QSA, Brisbane.

44. “Favour Referendums over Fluoridation: Six Mayors Want a Vote,” Sunday Mail, 5 July 1964, 5.

45. “BSC Too Democratic for Fluoridation,” Central Telegraph, 6 October 1960, 1. 46. “Fluoridation in Biloela,” Morning Bulletin, 13 September 1960, 5. 47. “Biloela Will Vote on Fluoridation,” Morning Bulletin, 25 July 1964, 1, 4. 48. Ibid.; “Senior Health Man to Come on Fluoridation,” Central Telegraph, 13 August

1964, 1. 49. Jack Harding, “Press Release to ‘Morning Bulletin’ and ‘ABC’ re the Biloela

Fluoridation Referendum, 6 October 1964,” Jack Harding Collection, Box 13, UQFL265. 50. Ibid.

51. Ibid; Jack Harding, “Fluoridation,” Morning Bulletin, 7 November 1964, np. 52. “May Halt Fluoride Scheme,” Courier–Mail, 4 February 1963, 3. 53. Ryan, “Written Communication.” 54. Ibid.

55. J. Seymour, “Written Communication to Dr. Noble, 5 July 1963,” Fluoridation Files, Series TR2027 FIR-FOO 1963–1981, Box 76, File 16, Item 16A, QSA, Brisbane.

56. A. Black, “Facts in Refutation of Claims by Opponents of Fluoridation,” Journal of the American Dental Association 50, no. 5 (1955): 655–64; Wilfred Stilwell, Norman Edson, and Percy Stainton, Report of the Commission of Inquiry on the Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies, Wellington, New Zealand, 1957, 151.

57. Attorney General of New Zealand v. Lower Hutt City Corporation (1964) New Zealand, AC 1469; “News and Comment: Fluoridation at Lower Hutt,” New Zealand Dental Journal 60, no. 282 (1964): 326–7.

58. Ibid.

59. Kelberg v. City of Sale (1964) Australia, VR 383; Head, 263–4; “Judge Stops Fluoride Plan at Sale; Authority Exceeded,” Age, 25 March 1964, 6.

60. Crisp, 250; J. Kenny, “The Legal Issues in the Fluoridation Case,” Journal of the Irish Dental Association 18 (1972), 56–8.

61. Commonwealth Department of Health, Fluoridation of Water: A Collection, 37–8; “Fluoridation to go Ahead but Must be Cleared First,” Courier–Mail, 2 November 1963, 3.62. Henry Winston Noble, “Queensland Cabinet Minute for Decision No. 5868— Submission No. 5157 for Cabinet, Fluoridation of Water Supplies, 15 November 1963,”Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Batch Files, Series SRS 1043�1, no. 633: Fluoridation

(part 1), Box 1036, QSA, Brisbane. 63. Western Australia Legislative Assembly, 1652, 2425. 64. Commonwealth House of Representatives, Debates 165 (1963). 65. Western Australia Legislative Assembly, 1449–50; “4–2 Decision By Water Board

Against Fluoride,” Sydney Morning Herald, 30 May 1963, 4. 66. Hunter District Water Board (NSW), Fluoridation of Water Supply—A55/232

(Newcastle: Hunter District Water Board (NSW), 1968), 4. 67. Colin Hughes, Images and Issues: The Queensland State Elections of 1963 and 1966

(Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1969), 1–322. 68. Queensland Legislative Assembly, Debates 236 (1963), 500–8, 587–600, 721–51,

1802–30. 69. Director of local government, “Written Communication to the Clerk—Mareeba

54 HARRY AKERS, SUZETTE PORTER, & RAE WEAR

Shire Council, 5 March 1963,” MA Simmonds’ personal archives, in author’s possession; Henry Noble, “Communication with Ministers of Queensland Cabinet—Submission No. 4901 for Cabinet, Fluoridation of Water Supplies, 29 August 1963,” Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Batch Files, Series SRS 1043�1, no. 633: Fluoridation (part 2), Box 1036, QSA, Brisbane.

70. Keith Spann, “Communication with Department of Health and Home Affairs; Minister for Health and Home Affairs; Chief Secretary’s Department and the Parliamentary Draftsman, Department of Local Government; Minister for Local Government; and All Other Ministers re Minute Decision No. 5577—Submission No. 4901 for Cabinet Fluoridation of Water Supplies, 2 September 1963,” Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Batch Files, Series SRS 1043�1, no. 633: Fluoridation (part 2), Box 1036, QSA,Brisbane.

71. Ryan, “Written Communication.”

72, Henry Noble, “Communication with Ministers of Queensland Cabinet—Submission No. 4901 for Cabinet, Fluoridation of Water Supplies, 29 August 1963,” Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Batch Files, Series SRS 1043�1, no. 633: Fluoridation (part 2), Box 1036, QSA, Brisbane.

73. Queensland Legislative Assembly, Debates 236 (1963): 500.

74. Seymour Tooth, “Cabinet Minute Brisbane, Decision No. 17880—Submission No. 1596, Proposed Amendment to ‘The Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Act of 1963,’ 20 November 1972,” Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Batch Files, Series SRS 1043�1, no. 633: Fluoridation (part 2), Box 1037, QSA, Brisbane, 1–4; Llewellyn Edwards, “Written Communication to Bundaberg City Council, 15 July 1975,” Bundaberg City Council Archives, in authors’ possession.

75. Fluoridation and the Local Authority (Brisbane: Queensland State Government, 1964), 1–8.

76. Ibid., 4 of appendix.

77. Brisbane City Council, Lord Mayor’s Taskforce on Fluoridation: Final Report (Brisbane: Brisbane City Council, 1997), 20; Greg Hallam, “Communication with Chief Executive Officer or Community Clerk of All Member Councils Re Fluoridation of Water, 5 June 1997,” Pat Jackman Archives (1997), in authors’ possession (hereafter PJA); Ella Riggert and Debra Aldred, “Fluoride Cities ‘Set for Legal Challenges,’” Courier–Mail, 2 October 1997, 5.

78. Brisbane City Council, 20.

79. Harry Akers and Su�ette Porter, “A Historical Perspective on Early Progress of Water Fluoridation in Queensland 1945–54: Sheep, Climate and Sugar,” Australian Dental Journal 49, no. 2 (2004): 61–6; Queensland Legislative Assembly, Debates 236 (1963): 736–7.

80. Queensland Legislative Assembly, Debates 236 (1963): 736. 81. Queensland Legislative Assembly, Debates 243 (1966): 159. 82. Chris Armstrong, “Dental Body Warns on Lawsuits,” Cairns Post, 10 May 1997, 5;

Anthony Morris, “Legal Opinion for ADAQ re Liability for Dental Fluorosis,” 12 March 1997, PJA, in authors’ possession.

83. Cameron Milner, Peter Beattie and Labor Keep Queensland Moving Dental Policy 2004 (Brisbane: Australian Labor Party, 2004), 1–2.

84. K.Archer,TheYearBookoftheCommonwealthofAustraliaNo.50:1964(Canberra: Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics, 1964), 802–16.

85. Queensland Legislative Assembly, Debates 243 (1966) 263; Wallace Rae, “Communication with the Under Secretary Premier’s Department: Ministerial Direction re Gympie Water Fluoridation, 7 May 1971,” Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Batch Files, Series SRS 1043�1, no. 633: Fluoridation (part 2), Box 1037, QSA, Brisbane.

86. John Moffatt, “Report of Interview with the Minister for Health, Dr. Noble, held on Wednesday 27 March 1963,” General File, ADAQ Archives, Brisbane, 1–4. There has been some confusion over Queensland subsidy. Barnard (1968) reports a subsidy of between 20 and 50 percent of capital cost. There is no Queensland subsidy to defray annual operating costs, but this is currently under review. On 16 October 2005, Premier Peter Beattie offered a 100 percent rebate for capital cost of introducing flfluoridation in communities

Water Fluoridation in Queensland, Why Not? 55

with populations over five thousand people. See P. Beattie, Media Statement: Premier’s Department—Beattie offers incentives to fluoridate water, 16 October 2005, Brisbane.

87. Banana Shire Council, Media Release: Banana Shire Council—Fluoridation and Biloela Water Supply, 2 July 2003.

88. Peter Beattie, Media Statement; Emma Chalmers and Michael Corkill, “Fluoridation Fund Tap Open Wide,” Courier–Mail, 17 October 2005, 1; Local Authorities of Queensland, Local Govt Rejects Beattie’s Fluoridation Brush-Off (Brisbane: Local Government Association of Queensland, 2005), 1.

89. Dan Nancarrow, “Fluoride Debate to Fire up Mayor Calls for a Vote,” News–Mail, 18 October 2005, 7; Paul Bell, “Handball to Councils,” News–Mail, 31 October 2005, 6.

90. Edwards; “Comment: Albert Shire and Fluoridation,” Beenleigh Express, 1 December 1960, 2.

91. Edwards, 2.

92. Seymour Tooth, “Cabinet Minute Brisbane, Decision No. 15727—Submission No. 13958, Fluoridation of Moranbah Water Supply by Utah Development Company, 20 April1971,” Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Batch Files, Series SRS 1043�1, no. 633: Fluoridation (part 2), Box 1037, QSA, Brisbane, 1–4 with appendix.

93. Wallace Rae, “Communication with the Under Secretary Premier’s Department: Ministerial Direction re Gympie Water Fluoridation, 7 May 1971,” Fluoridation of Public Water Supplies Batch Files, Series SRS 1043�1, no. 633: Fluoridation (part 2), Box 1037, QSA, Brisbane.

94. William Murison, “Fluoridation Referenda Statement Prepared for the ADA Victorian Branch, 29 February 1968,” Fluoride File, ADAQ Archives, Brisbane.

95. “Favour Referendums Over Fluoridation: Six Mayors Want a Vote,” Sunday Mail, 5 July 1964, 5.

96. Arthur Amies and Paul Pincus, “Fluorine and Dental Caries,” Australian Journal of Dentistry LVII, no. 5 (1953): 255–8

97. “Editorial,” Fluoride 28, no. 3 (1995): np; Philip Sutton, Fluoridation Errors and Omissions in Experimental Trials, 2nd ed. (London, Cambridge University Press, 1960).

98. “In Your Water,” Courier–Mail, 13 February 1960, 1.

99. Mark Diesendorf, “Is There a Scientific Basis for Fluoridation?” Community Health Studies IV, no. 3 (1980), 224–30; Mark Diesendorf, “Anglesey Fluoridation Trials Re-Examined,” Fluoride 22, no. 2 (1989): 53–8; Mark Diesendorf, “How Science Can Illuminate Ethical Debates: A Case Study on Water Fluoridation,” Fluoride 28, no. 2 (1995): 87–104; Mark Diesendorf, “The Mystery of the Declining Tooth Decay,” Nature 322, July 10 (1986): 125–9.

100. Mark Girard, “Queensland Water, Securing our Future,” Brisbane Line, Brisbane Institute, http://www.brisinst.org.au/resources/brisbane_institute_queensland_water.html (accessed 5 December 2005), 17 November 2005.

101. “Gatton to End Water Fluoridation,” Toowoomba Chronicle, 22 August 2002, np.

102. Richard Hofstadter, The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays (New York: Vintage Books, 1967), 314.

103. D.W. de Louth, “Fluoridation,” Fluoridation and Conspiracy 5 (1956): 1–4; D.W. de Louth, “Fluoridation,” Fluoridation and Conspiracy 1 (1957): 1.

104. JackHarding,“PoliticalZionism,”EmpirePatriotJuly(1951):27–9;JackHarding, “Our Queen and Our Freedom,” Monetary Reform League Contact Circular 50 (1954): 1–2;Jack Harding, “Freedom Petition,” Anti-Fluoridation Association Newsletter 29 (1968): 1–5.

105. Mark Diesendorf et al., “New Evidence on Fluoridation,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 21, no. 2 (1997): 187–90; G. Durham, “Review of Evidenceon Fluoridation,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 21, no. 5 (1997): 548; Peter Herbison, “Fluoridation,” New Zealand Dental Journal 93, no. 413 (1997): 93; John Colquhoun, “Correspondence: New Evidence on Fluoridation,” New Zealand Dental Journal 93, no. 414 (1997): 132; Peter Herbison, “Mr Peter Herbison Replies, New Zealand Dental Journal 93, no. 414 (1997): 132–3.

106. See “Australia Talks Back: Dental Health,” Radio National, radio program (Sydney: ABC Radio), 16 November 2005; [Media Monitors News Item B73462008], State

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!